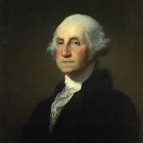

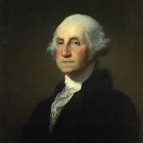

For any American, George Washington (1732–99) is—or ought to be—a man who needs no introduction. Commander-in-chief of the Continental Army in the War of American Independence (1775–83), president of the Constitutional Convention of 1787, and unanimously chosen to be the first president of the United States (1789–97), Washington has long enjoyed the deserved reputation as the Father of his Country. Universally admired for his courage, integrity, and judgment, Washington had great influence and power as the nation’s first president and hoped his tenure would set a lasting precedent for future leaders.

George Washington

As commander in chief, George Washington had to reckon not only with a dangerous enemy but also on occasion with uprisings among his men. Here, too, he performed superbly.

George Washington

As was evident from the beginning of his presidency (see, for example, his First Inaugural Address), George Washington was greatly concerned with the viability of our constitutional republic and, therefore, with the need to preserve and perpetuate our political institutions and culture of liberty.

George Washington

On November 2, 1783, the war officially concluded, General Washington delivered his farewell orders to the Armies of the United States of America at Rocky Hill, New Jersey. After more than eight long years as commander in chief, George Washington was returning to private life.

George Washington

George Washington’s famous Farewell Address was given in 1796, at the conclusion of his second term as President of the United States. But this earlier and less well-known speech of farewell is also of great significance, and it too repays careful attention.

George Washington

Presidential inaugural addresses have in our time become the occasion when newly elected (or re-elected) presidents, following custom, present in broad outline their visions of the national future and the plans for their administrations. As with everything else that he would do as president, Washington’s First Inaugural Address was unprecedented—and he spoke and acted accordingly.

George Washington

We celebrate the birth of the nation on the Fourth of July, the anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence. In doing so, we risk forgetting that the nation would have been stillborn had we not won the lengthy war of independence that lasted until 1781 and whose outcome was anything but assured.

George Washington

George Washington’s thoughts about the need for prompt constitutional reform may have been strengthened by the outbreak, in western Massachusetts, of Shays’ Rebellion in the early autumn of 1786.

George Washington

Three days after receiving his commission from the Continental Congress, General George Washington wrote this letter to his wife Martha. The letter may very well strike modern ears as overly formal and insufficiently affectionate.

George Washington

This selection provides an important example of President Washington’s thoughts on the important subject of religion, politics, and national well-being. Developing our unique blend of religion and politics, the American Republic self-consciously pioneered a novel approach to the problems of religious zealotry and religious conflict that have long plagued—and still plague—other nations.

George Washington

George Washington’s early thoughts about his retirement from public life are touchingly represented in this short letter, written from Mount Vernon on February 1, 1784 to the Marquis de Lafayette (1757–1834), the French commander who had served with distinction as a major general under Washington in the Continental Army.

George Washington

We know very little of what George Washington read or studied, or what subjects or ideas mattered to him as a young man. The present selection, concerning proper and gentlemanly conduct, is an important exception.

George Washington

The present selection, the Thanksgiving Proclamation of 1789, was Washington’s (and the nation’s) first presidential proclamation. Issued in the first year of his first term as president, in response to Congress’ request that he recommend a day of public thanks-giving and prayer, Washington used the occasion also to express, in yet another way, his views on the relation between piety and politics, as well as to promote practices that would stand the nation in good stead long after he was gone.

George Washington

After the Fourth of July, Thanksgiving Day is our most observed national holiday. The tradition harks back to the colonists of Plymouth Plantation, Massachusetts, who, after their first harvest, held a celebratory feast in the fall of 1621—a three-day celebration in which local Native American chiefs and tribesmen participated. But the first national Thanksgiving, authorized by the federal government, took place in 1789, the first year of George Washington’s presidency. President Washington issued this proclamation recognizing November 26 as “a day of public thanksgiving and prayer.”

George Washington