Introduction

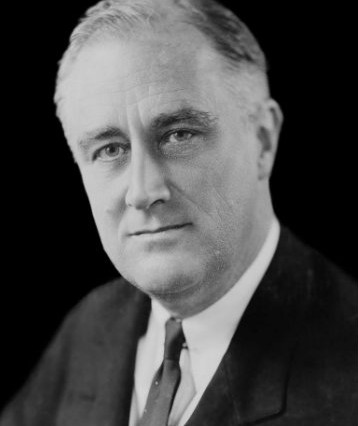

A rather different George Washington, invoked for a different purpose, is the subject of this radio address to the nation by our 32nd president, Franklin Delano Roosevelt (1882–1945), delivered in the dark days of the Second World War. Roosevelt appeals especially to the memory of how Washington “conducted himself in the midst of great adversities” in order to inspire his listeners to imitate Washington’s example. Roosevelt’s Washington emerges not as a military hero or noble gentleman, but as a man of faith, hope, and charity. Indeed, Roosevelt concludes by quoting the Beatitudes, which he calls “the words which helped shape the character and career of George Washington,” “the truths which are the eternal heritage of our civilization,” and our “guiding light . . . to the fulfillment of our hopes for victory, for freedom, and for peace.”

Why might Roosevelt, in the midst of World War II, invoke Washington’s faith, hope, and charity in order to inspire the American people? How closely does Roosevelt’s Washington resemble the Washington you have learned about from the historical record of his life and thought? Given Washington’s frequent references to the deity (see, for example, his First Inaugural Address, Thanksgiving Proclamation, and Farewell Address), is there some basis for Roosevelt’s picture and use of Washington? Do you find this speech inspiring? Why, or why not? Were you the leader of the United States in the dark days of war, how might you choose to speak on Washington’s Birthday?

Today this Nation, which George Washington helped so greatly to create, is fighting all over this earth in order to maintain for ourselves and for our children the freedom which George Washington helped so greatly to achieve. As we celebrate his birthday, let us remember how he conducted himself in the midst of great adversities. We are inclined, because of the total sum of his accomplishments, to forget his days of trial.

Throughout the Revolution, Washington commanded an army whose very existence as an army was never a certainty from one week to another. Some of his soldiers, and even whole regiments, could not or would not move outside the borders of their own States. Sometimes, at critical moments, they would decide to return to their individual homes to get the plowing done, or the crops harvested. Large numbers of the people of the colonies were either against independence or at least unwilling to make great personal sacrifice toward its attainment.

And there were many in every colony who were willing to cooperate with Washington only if the cooperation were based on their own terms.

Some Americans during the War of the Revolution sneered at the very principles of the Declaration of Independence. It was impractical, they said—it was “idealistic”—to claim that “all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable Rights.”

The skeptics and the cynics of Washington’s day did not believe that ordinary men and women have the capacity for freedom and self-government. They said that liberty and equality were idle dreams that could not come true—just as today there are many Americans who sneer at the determination to attain freedom from want and freedom from fear, on the ground that these are ideals which can never be realized. They say it is ordained that we must always have poverty, and that we must always have war.

You know, they are like the people who carp at the Ten Commandments because some people are in the habit of breaking one or more of them.

We Americans of today know that there would have been no successful outcome to the Revolution, even after eight long years—the Revolution that gave us liberty—had it not been for George Washington’s faith, and the fact that that faith overcame the bickerings and confusion and the doubts which the skeptics and cynics provoked.

When kind history books tell us of Benedict Arnold, they omit dozens of other Americans who, beyond peradventure of a doubt, were also guilty of treason.

We know that it was Washington’s simple, steadfast faith that kept him to the essential principles of first things first. His sturdy sense of proportion brought to him and his followers the ability to discount the smaller difficulties and concentrate on the larger objectives. And the objectives of the American Revolution were so large—so unlimited—that today they are among the primary objectives of the entire civilized world.

It was Washington’s faith—and, with it, his hope and his charity—which was responsible for the stamina of Valley Forge—and responsible for the prayer at Valley Forge.

The Americans of Washington’s day were at war. We Americans of today are at war.

The Americans of Washington’s day faced defeat on many occasions. We faced, and still face, reverses and misfortunes.

In 1777, the victory over General Burgoyne’s army at Saratoga led thousands of Americans to throw their hats in the air, proclaiming that the war was practically won and that they should go back to their peacetime occupations—and, shall I say, their peacetime “normalcies.”

Today, the great successes on the Russian front have led thousands of Americans to throw their hats in the air and proclaim that victory is just around the corner.

Others among us still believe in the age of miracles. They forget that there is no Joshua in our midst. We cannot count on great walls crumbling and falling down when the trumpets blow and the people shout.

It is not enough that we have faith and that we have hope. Washington himself was the exemplification of the other great need.

Would that all of us could live our lives and direct our thoughts and control our tongues as did the Father of our Country in seeking day by day to follow those great verses:

“Charity suffereth long, and is kind; charity envieth not; charity vaunteth not itself, is not puffed up,

“Doth not behave itself unseemly, seeketh not her own, is not easily provoked, thinketh no evil:

“Rejoiceth not in iniquity but rejoiceth in the truth.”

I think that most of us Americans seek to live up to those precepts. But there are some among us who have forgotten them. There are Americans whose words and writings are trumpeted by our enemies to persuade the disintegrating people of Germany and Italy and their captives that America is disunited—that America will be guilty of faithlessness in this war, and will thus enable the Axis powers to control the earth.

It is perhaps fitting that on this day I should read a few more words spoken many years ago—words which helped to shape the character and the career of George Washington, words that lay behind the prayer at Valley Forge.

“Blessed are the poor in spirit: for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

“Blessed are they that mourn: for they shall be comforted.

“Blessed are the meek: for they shall inherit the earth.

“Blessed are they which do hunger and thirst after righteousness: for they shall be filled.

“Blessed are the merciful: for they shall obtain mercy.

“Blessed are the pure in heart: for they shall see God.

“Blessed are the peacemakers: for they shall be called the children of God.

“Blessed are they which are persecuted for righteousness’ sake: for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

“Blessed are ye, when men shall revile you, and persecute you, and shall say all manner of evil against you falsely, for my sake.

“Rejoice, and be exceeding glad: for great is your reward in heaven: for so persecuted they the prophets which were before you.”

Those are the truths which are the eternal heritage of our civilization. I repeat them, to give heart and comfort to all men and women everywhere who fight for freedom.

Those truths inspired Washington, and the men and women of the thirteen colonies.

Today, through all the darkness that has descended upon our Nation and our world, those truths are a guiding light to all.

We shall follow that light, as our forefathers did, to the fulfillment of our hopes for victory, for freedom, and for peace.

Return to The Meaning of George Washington's Birthday.

Post a Comment