Introduction

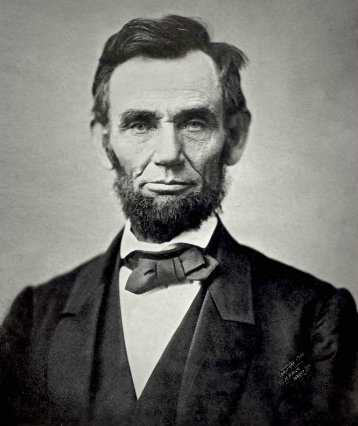

The creed of the American Republic, as enunciated in the Declaration of Independence, begins with the claim, offered as a self-evident truth, that “all men are created equal.” Yet our embrace of the principle was long embarrassed in practice by the existence of chattel slavery, present at the Founding but greatly increased through the first half of the 19th century. Critics of the Declaration openly called human equality “a self-evident lie,” and the infamous Dred Scott decision (1857) gave voice to a racist and exclusionary interpretation of the Declaration, insisting that its “all men” referred only to “all white men” who were the equals of British subjects living in Britain. No one did more to oppose this (mis)interpretation than our sixteenth president, Abraham Lincoln, who famously claimed that he had “never had a feeling politically that did not spring from the sentiments embodied in the Declaration of Independence.”1 Lincoln’s most famous defense of equality appears in the Gettysburg Address, delivered on November 19, 1863, in the midst of a civil war whose deepest cause was the institution of slavery. Here Lincoln revisits the Declaration of Independence, summoning the nation to achieve a “new birth of freedom” through renewed dedication to the founding proposition of human equality.

How does Lincoln understand the key terms of the creed, and in particular, the relation between equality and freedom? What is the difference between “holding” equality as a “self-evident truth” and regarding it as a “proposition” to which we are dedicated? What is the difference between the “new birth of freedom,” coming from the bloody war, and the original birth of the nation, “conceived in liberty”? How, according to Lincoln, can the war lead to a more perfect Union? What do you think is the meaning of equality today, and how is it related to freedom? How fares the idea and practice of “government of the people, by the people, for the people” in the United States today? How can we tell whether the Union today is being perfected or the reverse?

After you have read the Gettysburg Address and pondered these questions, you may want to read the analysis of the speech (“The Gettysburg Address: Abraham Lincoln’s Re-founding of the Nation”) by Leon R. Kass (b. 1939), coeditor of What So Proudly We Hail.

I think the authors of that notable instrument intended to include all men, but they did not intend to declare all men equal in all respects. They did not mean to say all were equal in color, size, intellect, moral developments, or social capacity. They defined with tolerable distinctness, in what respects they did consider all men created equal—equal in “certain inalienable rights, among which are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” This they said, and this they meant. They did not mean to assert the obvious untruth, that all were then actually enjoying that equality, nor yet, that they were about to confer it immediately upon them. In fact they had no power to confer such a boon. They meant simply to declare the right, so that the enforcement of it might follow as fast as circumstances should permit. They meant to set up a standard maxim for free society, which should be familiar to all, and revered by all; constantly looked to, constantly labored for, and even though never perfectly attained, constantly approximated, and thereby constantly spreading and deepening its influence, and augmenting the happiness and value of life to all people of all colors everywhere.

(8 votes, average: 3.38 out of 5)

(8 votes, average: 3.38 out of 5)

Post a Comment