Introduction

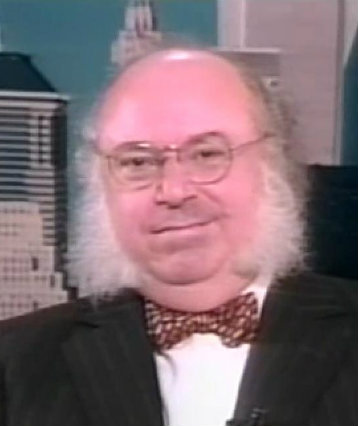

Independence had been won for the new nation, but the large problems of governance and political structure remained. As this selection by American author and editor Myron Magnet (b. 1944), excerpted from his 2012 essay titled “Washingtonianism” (two other excerpts appear in our Washington ebook) indicates, there was a growing sense that the original Articles of Confederation needed to be replaced if the new republic was to flourish. Although eager to continue in his retirement and enjoyment of private life, George Washington once again answered the call to public service. He presided over the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia, and, as Magnet points out, played a key role in the outcome.

What, according to Magnet, did Washington see as the defects and dangers of the Articles of Confederation? Why did he favor an “energetic central government” and growth of commerce? How might Washington’s presence at the Constitutional Convention have influenced the Constitution’s provision for energetic executive power? Although Washington was a proponent of a vigorous national government and an energetic executive, he distinguished between what Magnet calls (a) the machinery of government and (b) the culture of liberty. What is meant by each? How might they be related to each other? Why, and for what purposes, does a culture of liberty matter? Can its perpetuation be taken for taken for granted or does it require self-conscious cultivation? What does Washington mean by “the sacred fire of liberty,” and why is it so important for the preservation of the republic? Why does Washington believe that he will have to serve as the nation’s first president?

Post a Comment