Summary

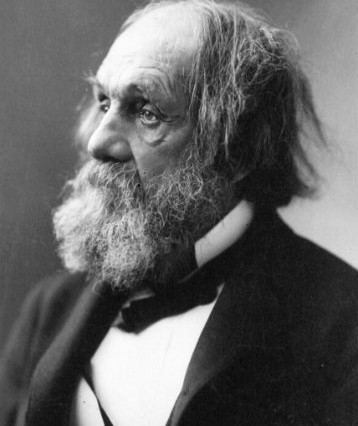

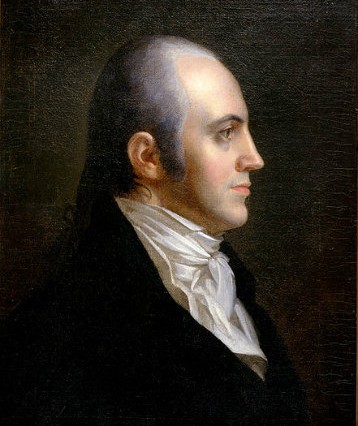

The plot of Hale’s story is straightforward: Seduced, “body and soul,” by the charm and grand vision of Aaron Burr, young Philip Nolan, an ambitious artillery officer in the “Legion of the West,” becomes a Burr accomplice (2–3). Tried for treason, “Nolan was proved guilty enough” (3). Still, no one would have heard of him “but that, when the president of the court asked him at the close, whether he wished to say anything to show that he had always been faithful to the United States, Nolan cried out, in a fit of frenzy,—

‘D—n the United States! I wish I may never hear of the United States again!’”

His judges, half of them veterans of the Revolutionary War, are stunned. They decide to give him precisely what he has asked for: From that moment, September 23, 1807, until his dying day, May 11, 1863—nearly fifty-six years later—Nolan is literally, and figuratively, put out to sea. He never again sets foot on American soil; only as he is dying does he again hear anything about the United States. Yet during—and perhaps because of—his enforced separation from his native land, Nolan’s attitude toward her changes dramatically. The rest of the story powerfully shows how his transformation comes about.

Section Overview

The story has a historical setting, but it is almost entirely fictional. Hale tells us his purpose both in the story proper and in the introduction he wrote for it twenty years after publication, to correct public misperceptions of the story’s historicity. In the text, the narrator, Fredric Ingham, says that his purpose is to show “young Americans . . . what it is to be A MAN WITHOUT A COUNTRY” (2). In the later introduction, Hale reports that he had hoped the story would be published before the 1863 elections, as he intended it not only “as a contribution, however humble, towards the formation of a just and true national sentiment, or sentiment of love to the nation,” but also as “‘testimony’ regarding the principles involved in [the election].” He had especially in mind the notorious activities of Clement Vallandigham, an ardent antiwar, pro-Confederate Ohio Democrat, then running for governor of Ohio from his exile in Canada. Some people believe that Hale’s story was in fact inspired by Vallandigham’s widely publicized assertion that he did not want to belong to the United States.

Only a couple of historical facts inform this otherwise fabricated tale about a purely fictitious character. After Aaron Burr left the vice presidency in 1805, he did make two trips down the Mississippi. Also, he and his accomplices were tried for treason. Burr was accused of a conspiracy to steal the Louisiana Purchase lands away from the United States and to crown himself as king or emperor. Despite the fact that US President Thomas Jefferson threw his full weight against Burr, the evidence available did not hold up in court, and Burr was acquitted. Not so for Philip Nolan, the fictitious protagonist of Hale’s story. Appreciating Nolan’s story requires us to try to understand, from the text alone, the young Nolan, the fate he was made to suffer, and his responses to it, from beginning to end. We need also to reflect on Hale’s stated purpose for writing the story.

A. Philip Nolan’s Early Life, His Crime and Punishment (1–6)

- Describe young Philip Nolan. What is he like as a young officer in the Legion of the West? What is the Legion of the West? (See pages 2–3.)

- Why do you think he is attracted so quickly and completely—“body and soul” (3)—to Aaron Burr, the man and, later, to his cause? What is Burr’s cause?

- Does the punishment he receives fit his crime (4)? If you think it doesn’t, what do you think a fitting punishment would be?

- What is Nolan’s initial attitude toward the punishment he receives (5)? Do you understand his reaction? Do you sympathize with it?

WATCH: Who is Philip Nolan? Why is he attracted so quickly to Aaron Burr, the man and, later, to his cause?

B. Charting Nolan’s Changing Attitude toward Home and Country

About each of the following incidents, please consider these general questions:

- What happened during the incident?

- What events led up to the incident?

- What is the meaning—what are the consequences—of the incident for Nolan?

- Why does it have such the impact on him that it does?

In addition, consider the following incident-specific questions:

Reading “The Lay of the Last Minstrel” (8–9). (Note: “The Lay of the Last Minstrel” [1805] is a long narrative poem by the Scottish poet Sir Walter Scott. A canto is a main division of a long poem; the word comes from Italian, meaning “song.”)

- What does Sir Walter Scott’s poem mean? Why and how does it affect Nolan? See, specifically, Canto 6, including the last four lines which are not referred to in Hale’s text.

Rebuke from his dancing partner, Mrs. Graff (10–11).

- Does Nolan’s acquaintance with a person like Mrs. Graff, back in Philadelphia before her marriage, shed any further light on Nolan’s former life?

- What kind of person do you think Nolan was back then? What kind of society did he belong to?

Nolan’s receipt of the “sword of ceremony” for his splendid and courageous action in the frigate (=warship) duel with the English (11–12).

- What do the tears Nolan sheds here tell us about the state of his soul?

- Why might the receipt of the “sword of ceremony” be both especially meaningful and especially painful for Nolan?

Nolan’s confrontation with the newly freed African slaves (15–17).

- Nolan’s ability to take on this job is due to his knowledge of Portuguese. Does his knowledge of the language surprise you? What can we infer about the type of upbringing and education Nolan had growing up? What kind of family do you think he came from?

- What role does Nolan play in their emancipation?

- Why is Nolan’s agony especially moving here?

The speech to young Fred Ingham (16–17).

- What significance does Nolan here attach to “home and country”?

- What really has he come to long for?

Nolan’s deathbed exchange with Danforth and the “little shrine” in his stateroom (20–23).

- Why did Danforth, so forthcoming in many other ways, decide not to tell Nolan about the Civil War?

- Why did Nolan take such pleasure in discovering that the then-president of the United States, Abraham Lincoln, was a man of the people, not a man of privileged birth?

- Nolan dies with his father’s badge of the Order of Cincinnati pressed to his lips. (The Order of Cincinnati is an eagle-shaped badge to be worn by veterans of the Revolutionary War.) What is the meaning of this gesture?

- Was Nolan a man without a country? Why or why not?

WATCH: How does Nolan's punishment affect him?

C. Hale’s Purposes

- Despite Hale’s insistence that the story is fictional, as noted earlier, we do know when it is written—during the height of the Civil War, in the year of the Emancipation Proclamation. Is its Civil War background important for understanding the story’s meaning?

- If you regard the background as key, is the story anything more than a piece of wartime propaganda? Why do you answer as you do?

WATCH: Is its Civil War background important for understanding the story's meaning?

The video seminar helps capture the experience of high-level discourse as particpants interact and elicit meaning from classic American texts. To watch the full conversation, click here. Otherwise click below to continue.

(9 votes, average: 3.44 out of 5)

(9 votes, average: 3.44 out of 5)

Post a Comment